👆For non-paid members, the clip above is a free preview. The complete lecture is available to paid members of EndoCollab.

The 11 O'Clock Rule and Other Secrets You Weren't Taught

A difficult biliary cannulation can turn a routine ERCP into a frustrating, high-risk procedure. We've all been there—struggling with a tricky papilla, repeatedly cannulating the pancreatic duct, and watching the clock. But what if the core of the problem lies in a fundamental misunderstanding of the papillary anatomy that most of us learned from textbooks?

This article revisits the foundational principles of biliary cannulation, revealing that the key to success isn't just about finding the orifice, but understanding its hidden structure. We'll explore the crucial "11 o'clock" rule, the concept of the biliary "septum," and advanced scope-handling techniques that can dramatically improve your success rate.

The Anatomical Surprise: It's Not (Usually) a Common Channel

The first step to better cannulation is knowing the history and anatomy. While we call it the Sphincter of Oddi, it was Glisson who first described the muscle fibers at the outlet of the bile duct back in 1654. The very terms we use—papilla (an opening or protuberance) versus ampulla (a bleb)—reflect different ways of seeing this structure. Surgeons often prefer ampulla to avoid confusion with other papillary cancers, like those in the thyroid.

The most critical anatomical insight, however, is that the classic textbook image of a single orifice leading to a long common channel is often wrong.

Clinical Pearl: The Myth of the Common Channel

Dissection specimens show that the bile duct and pancreatic duct typically have distinct outlets or, at best, a very short common channel. In up to 30% of people, the outlets are completely separate. This anatomical reality is essential for cannulation.

This separation is created by a septum, which divides the two ducts. The sphincter itself is not a single ring of muscle but a complex, figure-of-eight structure with separate sphincters for the bile duct and the pancreatic duct.

A cross-sectional diagram of the Sphincter of Oddi is shown. It clearly illustrates two separate ductal lumens within the sphincter complex. The bile duct is positioned superiorly at the 11 o'clock position, while the pancreatic duct is located inferiorly and contralaterally. A distinct tissue septum separates the two. This visual reinforces that cannulation is not about finding a single hole, but targeting a specific ductal orifice.

The speaker explains that pushing your catheter or sphincterotome against this central septum can induce spasm in both sphincters, making cannulation more difficult and increasing the risk of false tracking or accidental pancreatic duct cannulation.

Positioning for Success: It's About the View, Not the "J"

Before you even approach the papilla, proper setup is key.

Practice Points:

Clear the Field: Remove any dirt, water, or bubbles that obscure your view.

Find the Papilla: Use insufflation and the tip of your catheter to gently move folds if the papilla is hidden.

Optimal Positioning: The ideal position for the papilla is in the upper third of the endoscopic view and in the middle of the screen. This provides the best stability and angle for cannulation.

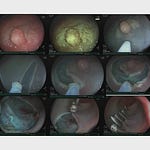

The video shows a papilla perfectly positioned for cannulation. It sits comfortably in the upper third of the screen, centered horizontally. This positioning allows for a straight, stable approach with the endoscope and instruments, maximizing control and visibility.

A common pitfall is obsessing over achieving a perfect "J-shape" or "hockey stick" position with the endoscope. The speaker emphasizes that successful cannulation depends on the endoscopic view, not a specific endoscope shape. Forcing a J-shape can sometimes lead to an unstable position.